Retrospective Report | Summary

Restrospective - Progress in the ACT between 2004 AND 2013 [PDF 1.6MB] (full report)

About the Children and Young People Death Review Committee

The ACT Children and Young People Death Review Committee is established under the Children and Young People Act 2008 to better understand and work to reduce the number of deaths of children and young people in the ACT. The Committee reports to the Minister for Children and Young People.

The legislation requires the Committee members to have experience and expertise in a number of different areas, including paediatrics, education, social work, child safety products and working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people.

The Committee wants to find out what can be learnt from each child’s or young person’s death that might help prevent similar deaths from happening in the future.

In order to do this, we keep a register of the deaths of ACT children and young people who die before they turn 18. We can then use this information on the register to learn more about why children and young people die in the ACT.

Based on what we learn, we can then make recommendations about changes to legislation, policies, practices and services to both government and non-government organisations.

The Committee does not investigate or determine the cause of death of a particular child or young person. We do not place blame or seek to identify underperformance. We do seek to help raise awareness of potential dangers for all ACT children as well as providing prevention messages among professionals and in the broader community.

To help us with our work, we are keen to hear from people in the ACT who are prepared to share their ideas and thoughts resulting from their own experiences and observations related to the death of a child in the ACT.

If you think your experiences would benefit other families, please get in touch with the Committee

Retrospective review: in brief

The retrospective review is a look at the progress we have made as a community over a period of 10 years. Reflecting on changes that occurred over time is a way for us to better understand trends. The review uses a social determinants of health (SDoH) approach to analyse the data on the deaths of children and young people and how our community, systems and supports have worked to influence trends over time.

Complete data for the age cohort 0–17 years is at Appendix A. This includes all children and young people recorded on the Children and Young People Deaths Register between 2004 and 2013. This review analyses the data for children and young people aged between 28 days to, and including, 17 years. Detailed analysis of the very young child deaths (within the first month of life) is undertaken by the Perinatal Mortality Committee and their reports can be found on the ACT Health website.

The World Health Organization describes the social determinants of health as...

the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life. These forces and systems include economic policies and systems, development agendas, social norms, social policies and political systems.[1]

What this means is that our community, systems and supports influence how we live and how we live, in its turn, influences our community.

The ACT Children and Young People Death Review Committee (CYPDRC, the Committee) established a framework based on the SDH philosophy to more closely examine the trends in deaths of children and young people in the ACT context.

The legislation requires the Committee to report on the ages, gender and child protection status of children and young people whose deaths occurred between 2004 and the establishment of the Committee in 2012. The Committee’s function is to help the community become more aware of how and why children and young people in our community are dying, and to make recommendations to help prevent or reduce the likelihood of the death of children and young people in the future.

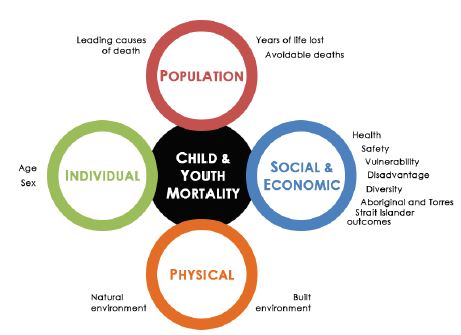

The framework used looks at four different areas, which we’ve called domains. The data are analysed from the perspective of a total population; social and economic wellbeing; physical settings in which we are active; and individual level characteristics. Within these domains are a number of indicators that relate to a particular aspect of the domain and that map to important characteristics of the community or the way people live. The framework is described in greater detail later in the review.

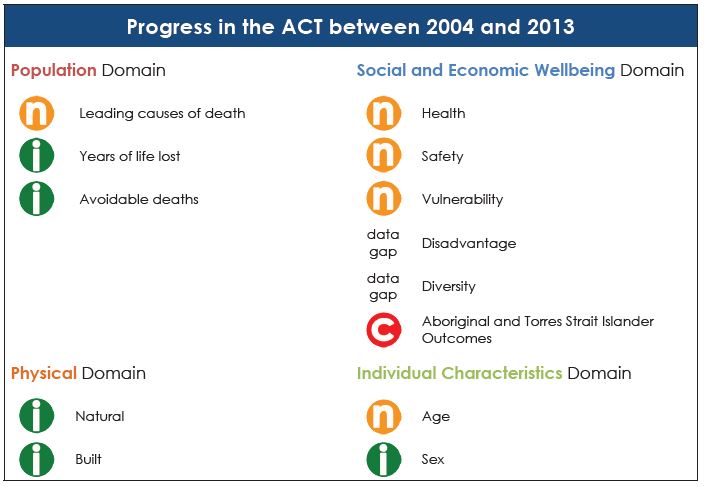

By looking at how things have changed in each of these domains over a 10-year period we can see positive trends, areas where trends hardly changed and areas where we could be doing better as a community. On the next page is a diagram of all the Domains and the associated indicators that marks where things improved, where there was no change in trends and where trends are concerning.

Improving

No change

And finally, when an indicator is concerning

The Committee’s analysis shows that there are areas where the ACT performed well and areas where improvements could be made.

For instance, in the Population Domain the leading causes of death remained relatively unchanged over the 10 years whereas those deaths that were avoidable and related to lifestyle and behaviours reduced.

In the Social and Economic Wellbeing Domain, trends did not change. Generally, the trend in health and safety indicators for children and young people remained unchanged, but in the factors that help shape our community the ACT did not perform well—Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were over-represented in the cohort. Broader cultural diversity data were not recorded for the 10-year period under review and was identified as a data gap.

Progress was made, on the other hand, in the Physical Domain indicating that systemic changes and public safety messages were effective over the period. This trend is no cause for complacency, however, as drowning and transport accidents continue to occur. The ACT’s positive trend over the period in this domain differs from the national trend, which showed an increase in deaths from interactions with the physical environment. [2]

There was no real change in trends for age, with the early years of childhood and the later years of adolescence showing high risk in both 2004 and 2013. Meanwhile, for the Sex indicator, there was a substantial amount of fluctuation over the period though there did seem to have been a greater reduction in male deaths.

The key recommendation flowing from this report is for Government and related services to improve the systems and culture for sharing information in the interests of protecting vulnerable children. A range of reviews and reforms has been implemented by the Commonwealth and ACT governments in recent years which will have partially or fully addressed some of the areas for reform identified in this report.

The Committee also identifies the need for more work in the following areas. The Committee will continue to:

- work with stakeholders to influence how information is shared by relevant parties to facilitate a stronger system to prevent children from experiencing multiple vulnerabilities

- engage with key stakeholders to discuss practical issues that will facilitate a better understanding of child and youth mortality, such as improving the accuracy of death certificates

- identify opportunities to raise awareness on the specific issues relating to child and young people deaths already identified by the Committee, such as the risks of co-sleeping with an infant

- monitor trends in child and youth mortality and report findings to the community

- examine all aspects of mortality and contributing factors by continuing to build and maintain a comprehensive Children and Young People Deaths Register, including improving the indicators of disadvantage and diversity

- report to the ACT Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elected Body in its role as a democratically elected voice for the people in relation to findings on the deaths of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people in the ACT

- work with the Australian and New Zealand Child Death Review and Prevention Group on issues that are relevant to all.

The Committee will continue to work to better understand child and youth mortality in the ACT. It will use that knowledge to identify where systemic changes can be made to improve the health, wellbeing and outcomes for all children and young people in the territory.

Introduction

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare states that collecting and analysing data on the deaths of people in Australia is useful for: [3]

- understanding death and the fatal burden of disease in the overall population at a point in time

- monitoring trends in death, specific causes of death and life expectancy over time

- investigating differences between population groups such as people living in areas of different remoteness and socioeconomic status, people born in different countries, and Indigenous people

- informing health policy, planning, investment and administration of the health care system across all its tiers, including in relation to population health interventions and health system changes.

In short, understanding how, where and why we die helps us reduce and prevent those deaths which are premature and avoidable, as well as helping all of us live safer lives.

In the 10 years between 2004 and 2013 there were 1,404,702 deaths recorded in Australia.[4] Of those, 19,420 were children and young people under the age of 18 years.[5] In the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) there were 354 deaths of children and young people over this period. The population that this review focuses on are those children and young people who died in the ACT, excluding those deaths that occurred in the neonatal period (which are investigated separately in the Perinatal Death Report) as well as those infants, children and young people whose deaths were subject to a current coronial inquiry at the time of reporting. This excluded group will be mentioned in the discussion of Age, later in this review. The primary analyses include 128 children and young people under the age of 18 years. Consistent with the Committee’s legislation, analyses have been limited in some areas so that individuals cannot be identified.

To be clear, the cohort of infants whose deaths occur in the neonatal period are an important part of understanding child mortality in the ACT. They have been excluded from this report for two main reasons: firstly, the factors surrounding these deaths are covered in detail by the ACT Perinatal Mortality Committee; and secondly, because the relative number of these deaths, in comparison with other cohorts, can often overwhelm some of the issues for the full age cohort. The Committee wishes to acknowledge the experiences of families who have lost a child in that period, however, and examines some of the factors related to this group in the Individual Characteristics Domain section of the report.

The ACT Children and Young People Death Review Committee (CYPDRC, the Committee) has chosen to examine deaths in the 10 years to 2013 in the context of our community and the way we live our lives. The Committee has taken this approach to learn what we can about the children and young people who have died over this time, so that we can then inform our community in a way that is relevant and helpful, and make recommendations about practical changes. This review acknowledges the work of the Measures of Australia’s Progress report from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, as it has been a strong influence on the development of this review.[6]

Measuring our progress

Reflecting critically on trends occurring over time is one way for us to better understand the direction we have taken. Using mortality rates and understanding how changes in those rates over time relate to the way we live our lives, gives us crucial information on how our community is progressing. Importantly, understanding the links between death and our social make-up helps us to recognise what can be done to reduce preventable deaths.

Significant improvements in health systems over the last century have considerably reduced the incidence of child deaths. [7] While raw numbers have reduced markedly, we now look at the data differently. Despite greater emphasis on the visibility of children and young people and on their right to have their voices heard, children, and to a lesser degree young people, have limited capacity to influence the conditions in which they live. UNICEF concedes that ‘Article 12—the provision that children have a right to express their views and have them taken seriously in accordance with their age and maturity—has proved one of the most challenging to implement’. [8] Consideration of how our community actions actually affect those in our community with the least power (our children) could possibly serve as a litmus test of sorts to measure how we are functioning as a community and what might need to change.

In this review the Committee considers the burden of mortality as one indicator of whether the ACT population is benefiting from the ways we are currently choosing to develop our community, systems and supports. If we consider the deaths of our children more broadly, that is, by considering the causes of the causesof death [9] and explore such issues as poverty, inequality, access to health care, greater exposure to risks and so on, this might provide further insight into the social and environmental conditions in which we all grow and develop.[10] In turn, this might give us better information about where we need to make changes in order to maximise the overall health and well-being of our community.

The CYPDRC has previously reported ACT levels of child and youth mortality to be low. In a perfect world the only deaths of children and young people would be those from causes beyond the capacity of current medicine and outside the comprehension of other protective mechanisms we’ve established for ourselves; that is, essentially, unavoidable deaths. Sir Michael Marmot of the World Health Organization’s Commission on the social determinants of health argues that where a child dies and that death could have been avoided, that society is not maximising the resources available to ensure that health, and by extension the prevention of death, is equitable.[11]

To that end, there are three things a government can do to minimise loss through inequitable or avoidable deaths: it can guarantee human rights and access to essential services; it can facilitate policy frameworks, legislation and regulation that provide the framework for equity; and finally, it can gather and monitor information about populations that generate information to educate the populace about themselves and inform the other two roles. [12]

It is the latter of these roles that underpins the central function of the Committee—to monitor child and youth mortality—so that our community has the information on which to act. The underpinning hypothesis is thatchildren and young people dying prematurely from avoidable deaths in our community is a direct indication that the community is not maximising the social arrangements and that those arrangements must be amended.[13]

Social determinants of health framework

To analyse trends in a meaningful way, the CYPDRC has adapted the social determinants of health (SDoH) philosophy promoted by the World Health Organization. This philosophy acknowledges that the prevention of mortality among children and young people is not the sole responsibility of any one agency. A multitude of factors make the minimisation and prevention of child and young people deaths the responsibility of all arms of government and all branches of society. [14] A SDoH approach to monitoring child and youth mortality, linking as it does with our social constructs—the way people live in the world—can bridge the divide between various interventions and agents by returning to multi-accountability of action. That is to say, we are all responsible. A SDH philosophy acknowledges that we live in dynamic environments, each interacting with and affecting another. By considering the multi-faceted way in which our ‘many selves’ exist, a SDH approach can help shift the balance from reaction to prevention, requiring as it does to take a broader view of an issue, and offers a positive outlook for equitable and sustainable outcomes. [15]

Thecauses of the causesare also better identified through a SDH framework. People live and work in a social hierarchy that affects their individual exposure to risks and also shapes their responses to it. Linking mortality to constructs that shape our society can give us a greater understanding of the effects and distribution of mortality than another model such as a purely medical model might otherwise provide. Health, and therefore mortality, follows a social gradient and it would be remiss of the Committee not to consider mortality in the broadest sense, to better determine how to prevent it.[16]

The CYPDRC acknowledges that mortality is one lens through which to consider our progress and that other lenses will add to the evidence and discussion about the progress of the ACT. However, given the cost to life, the loss to families and the cost to our community through reduced social and economic participation, the more we can understand about how and why children and young people die, the better we are equipped to prevent it. The evidence produced in this review should be considered in conjunction with additional population-level information on health and wellbeing, for example, morbidity and welfare-based reports.

In summary, a SDH framework considers the broader circumstances in which people live, work and play. It acknowledges the social structures and the external factors that influence people’s behaviour as well as those unchangeable individual factors, such as sex and age, that also affect outcomes. To that end, the CYPDRC has adopted the following framework to assess progress. This framework includes domains on population-level characteristics, social and economic constructs, the physical environment and individual characteristics.

Social Determinants of Health: Children and Young People Mortality Framework

Population Domain

Population Domain This domain allows for the collective effects of premature mortality to be considered. It looks at the potential years of life lost and potentially avoidable deaths. It also looks at the leading causes of death. On the basis of these summary indicators we are able to determine an overall indication of the effects that premature mortality has on the ACT community.

Social and Economic Wellbeing Domain

This domain includes indicators that link to a number of social factors—factors that help shape our ability to participate in the community, both socially and economically. By investigating mortality in relation to those indicators we are able to determine if there are inherent inequalities or trends that could be remedied to prevent further deaths.

Physical Domain

This domain provides information about the tangible environments in which we operate. While the previous domain focuses on factors that shape our society, this domain focuses on the way we move and operate in a physical environment. By looking at this domain we can determine if there are lessons to be learned to prevent further deaths caused by the physical environment.

Individual Characteristics Domain

This domain looks at those unchanging characteristics that shape and affect the forces that exist in the other domains. By examining these characteristics we can determine if there are cohorts that are particularly affected by mortality.

How to read this review

Review structure

This review is structured to align with the Social Determinants of Health: Children and Young People Mortality Framework, as described above. Each chapter is dedicated to a domain and each indicator is reported with the following information:

- Why is it important?

This section demonstrates how the stated indicator aligns with ACT societal expectations. It helps to provide a context for how the indicator measures the impact on lives in the ACT and, as a community, what systems and supports we decide are important.

- How have we measured it?

This section describes the data that were used to determine if there was a change. Health cannot be observed unless it is defined in some way that can be observed, such as illness and disease. Each indicator has been defined using data from the ACT Children and Young People Deaths Register which is maintained by the CYPDRC.

- How have things changed?

The period under review is between 2004 and 2013. Where possible, data have been provided as a time series to demonstrate trends. Summarised data were used where the number of deaths is small to avoid the identification of individuals.

- Further committee action

This section outlines key future actions for the Committee to influence policy, change systems, or help the community become more aware of the issues.

- Vignette

Throughout the report vignettes are featured. These are short commentaries from committee members on topics that highlight, exemplify and otherwise lend support to the issues. These vignettes arise from the extensive experience and expertise of committee members and are provided to broaden the understanding of indicators and findings.

Indications of change

The purpose of this review is to determine how the ACT has progressed over the 10-year period to 2013. We have used mortality trends in children and young people as the basis to determine whether progress has been made. Each indicator has been assigned a progress marker as follows:

Improving there has been a reduction in mortality over time.

No change the rates of mortality have remained the same over time.

Concerning there has been an increase in mortality over time or levels are above what might be reasonably expected.

Time series: leading three-year averages

The period under review is 2004–2013 inclusive. However, given that the mortality rates in the ACT are small in number and the Committee undertakes to protect the confidentiality of children and young people who have died, as well as their families, data in this report have been provided as leading three-year averages. Readers will note that graphs begin at 2006; this is due to the effect of averaging the preceding years. This process helps to minimise the effects of fluctuating data, allows for greater reporting of figures where possible (which in other cases would mean that data would be suppressed), and protects the confidentiality of young people and their families. This is consistent with the requirements of the legislation.

References

1 World Health Organization 2016. Social determinants of health. Geneva: WHO. Viewed 13 November 2016, <http://www.who.int/social_determinants/en/>.

2 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016. Table 1.2 Underlying cause of death, all causes, Australia, 2005–2014.In: ABS 2016. Causes of death, Australia, 2014. Cat. no. 3303.0. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 13 November 2016, <http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/3303.02014?OpenDocument>.

3 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2016. Deaths. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 13 November 2016, <http://www.aihw.gov.au/deaths/>.

4 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2015. Table 21.1 Deaths, Sex, Age (single years), Australia, 2004 to 2014. In: ABS 2015. Deaths, Australia, 2014. Cat. no. 3302.0. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 13 November 2016, <http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/3302.02014?OpenDocument>.

5 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2015. Table 21.1 Deaths, Sex, Age (single years), Australia, 2004 to 2014. In: ABS 2015. Deaths, Australia, 2014. Cat. no. 3302.0. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 13 November 2016, <http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/3302.02014?OpenDocument>.

6 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2014. Measures of Australia's progress, 2013. Cat. no. 1370.0. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 13 November 2016, <http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/1370.0>.

7 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2016. Age at death. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 13 November2016, <http://www.aihw.gov.au/deaths/age-at-death/>.

8 Lansdown G 2011. Every child’s right to be heard: a resource guide on the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child general comment no. 12. London: Save the Children UK. Viewed 13 November 2016, <http://www.unicef.org/french/adolescence/files/Every_Childs_Right_to_be_Heard.pdf>.

9 Blaus E, Gilson L, Kelly MP, Labonté R, Lapitan J, Muntaner C et al. 2008. Addressing social determinants of health inequities: what can the state and civil society do?. The Lancet 372(9650):1684–9. Viewed 13 November 2016, <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61693-1>.

10 Marmot M 2007. Achieving health equity: from root causes to fair outcomes. The Lancet 370(9593):1153–63. Viewed 13 November 2016, <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61385-3>.

11 Marmot M 2007. Achieving health equity: from root causes to fair outcomes. The Lancet 370(9593):1153–63. Viewed 13 November 2016, <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61385-3>.

12 Blaus E, Gilson L, Kelly MP, Labonté R, Lapitan J, Muntaner C et al. 2008. Addressing social determinants of health inequities: what can the state and civil society do?. The Lancet 372(9650):1684–9. Viewed 13 November 2016, <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61693-1>.

13 Marmot M 2005. Social determinants of health inequalities. The Lancet 365(9464):1099–104. Viewed 13 November 2016, < http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(05)71146-6/abstract >.

14 Marmot M 2007. Achieving health equity: from root causes to fair outcomes. The Lancet 370(9593):1153–63. Viewed 13 November 2016, <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61385-3>.

15 Marmot M 2007. Achieving health equity: from root causes to fair outcomes. The Lancet 370(9593):1153–63. Viewed 13 November 2016, <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61385-3>.

16 Marmot M 2005. Social determinants of health inequalities. The Lancet 365(9464):1099–104. Viewed 13 November 2016, < http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(05)71146-6/abstract >.